- John C Flavin | Personal Essays

- Posts

- "Be Honest and Make No Pretense"

"Be Honest and Make No Pretense"

A hundred and seventy-five years ago in 1994 at the University of Washington...

Topics

Not political. Humor, language, life story, essay as a genre, history of the essay, brief references to teaching

A Bit About This Personal Essay:

I’m in the middle of Goucher College’s Creative Nonfiction graduate program. I submitted this essay for a class, but it is not typical of what I intend to post on this site. What I do hope to publish are personal stories as a compilation for a full-length book: a memoir-in-essays.

This is an essay about the definition of an essay, so the likely audience is narrow. But if you’re interested in the history and language of what constitutes the genre, along with some playfully shared personal anecdotes, then this lighthearted piece might work for you.

It’s told from my perspective as a high school English teacher and how I discover that my understanding of the genre, the essay, is sadly basic and incomplete. At my age and at this stage of my career, how the hell did this happen?

25-30-minute read

“Be Honest and Make No Pretense”

"An essay is a structured way of sharing information.”

What Is an Essay? No, Really, What Is an Essay?

I have a story, or stories, to tell, and a predicament has been understanding the difference between two forms—essays and memoirs—and then deciding which is best for my writing. Before I started the Creative Nonfiction Writing Program at Goucher College, being an English teacher, I thought the difference was not so full of drama. Essays are more research-based and memoirs are more memory-based; essays are more objective while memoirs are more subjective; essays are shorter, and memoirs are longer. Also, one can write an essay about someone or something else but not so in a memoir. Clearly, I was missing something.

My problems started to swell on my first day of the 2024 Summer Residency while everyone energetically unpacked their bags and computers. I overheard an open discussion about it. In a sunny room with floor-to-ceiling windows, there were eight or nine other students, three mentors, and the director (also a mentor) of the program. Most knew each other from past semesters, and our spirits were high. Based on my assumptions stated above, I anticipated a precise, sterile, and efficient delineation, whereby one of the mentors might state it as cleanly as a dentist polishes her patient’s gleaming white teeth. Others would nod and approve, and then we’d open our readings and have a nice literary discussion. Instead, there was a brief clarification about length differences, but disagreements persisted, and I piped up to say, in so many words, “Essays are more fact-based. They include research about issues or events outside of the person’s memory, and memoirs rely more on memory but can use facts or statistics.” (I probably wasn’t that articulate, but this is an essay, which means I can approximate when necessary, so long as my reader doesn’t call bullshit.) One of the mentors called bullshit and shot my little thought down like a quail flushed from the bushes: “No, I don’t think so.” Those were her words, but what I heard was, “Back off, teacher-boy.”

Teacher Picture, Kenwood High School, 2023

It was nothing like that, of course, because the mentors of the program don’t treat people that way. I was being sensitive, and it only felt that way because, as an English teacher, I have an unwritten obligation to know all things related to language, including, and perhaps especially, the distinctions among genres.

I got over it, but my long-held assumptions about the two genres had been placed on unpaid administrative leave. Instead of feeling discouraged, it sparked my need to find out. Because I didn’t hear the mentors coming to clean and sterile agreements, it became murkier. I have since read and listened to everything I could. During the ensuing fall semester and Winter Residency in New York City, I listened to professional writers and classmates as if every next sentence might hold key points about the clear indicators of the genres. I discovered that the apparent father of the modern essay is 17th century writer Michel de Montaigne. Virginia Wolff’s and Joan Didion's names came up a lot, as well as a few well-known and unknown professors. I searched for a baseline from which to begin my education of the genre so I could gain a clearer understanding. The more I researched though, the once-clear, once-murky definition of an essay then became a moving target. It almost seemed like the experts were purposely trying to be less clear. I felt like the cliché, dumbstruck detective staring at a suspect board crammed with headshots, tacks, and colored yarn. Some English teacher I was.

But, in the spirit of an educator, I did what I would typically do when introducing a complex topic to my 10th- graders: collect concrete details to create a baseline understanding.

Here is that baseline:

Essay: a piece of writing, rarely more than 100 pages, that expresses a relatively narrow aspect of the writer’s position on any topic. It may be written objectively or subjectively or any combination of the two, casually or formally or any combination of the two, and from memory or by investigation or any combination of the two.

In short, an essay is nonfiction that may be two pages or a hundred. It is not a clean genre.

My search for concrete descriptors was like Googling John Smith. Ambulatory and drifting, the essay may arrive at your door in a fresh new suit or with filthy toes sticking out of his shoes. He has few obligations, particularly if one compares him to fiction or poetry. Fiction may have a range of subgenres, such as science fiction, but the genre is prose that describes imaginary events and people. That’s it. Poetry is an endlessly complicated craft with innumerable possibilities in form and style, and yet one only needs to see it in print to tell it apart.

Actual AI rendition of the essay

Eventually, the distinction between essays and memoirs became less important because defining memoirs is substantially simpler, and anyway, I had decided on essays as my craft for the program. If I intended to write a compilation of essays, I needed to know what the genre expects, and therefore, this is the result of my search for its shapeshifting identity.

^ ^ ^

“Half the articles published are propaganda, political, economic, social; the other half are purely informational, mere catalogues of fact. The essay is nowhere.”

Katherine Fullerton Gerould, Essayist, 1935

What Essay Experts Say, and Don’t Say

If I told the average person that I was writing an essay, they might assume it involves research on a topic assigned by the professor—whatever the subject. Knowing it’s an English-related course, they might expect that I would be asked to compare or contrast authors. If I were writing about fiction, they would imagine familiar names of writers, like John Steinbeck or Toni Morrison. I might write something like:

In the novel by Toni Morrison called Beloved, she uses imagery to magnify the metaphor of the power of memories. She writes, “He looked at her then, closely. Closer than he had when she first rounded the house on wet and shining legs, holding her shoes and stockings up in one hand, her skirts in the other (Morrison 186).”

And then I would follow with objective analysis: “One might argue that...”. And so on.

But if I wanted to show how an author of essays articulates metaphors to represent memories (same essay prompt), the average person would likely not expect it to read:

In a book of essays by Lauren Hough called Leaving Isn’t the Hardest Thing, she uses imagery to magnify the metaphor of the power of memories. “After the night Jay’s shockingly hairy ass landed on my face, I learned to sleep with my head to the door (Hough 66).” One might argue that...

And so on.

The similarities, one fiction and one nonfiction, are telling. If one didn’t know either piece of writing or their authors, there would be no way to discern them. It could even be argued that Hough’s essay sounds more like fiction than Morrison’s novel. I don’t think so, but it could be argued.

Knowing Morrison’s work, her words fulfill common expectations because anything goes so long as the scene is imagined. It remains clearly fictional whether one identifies it by a subgenre, such as historical, science, or any other. It illustrates how the genre is easily identifiable and, unlike this essay which attempts to define an essay, it wouldn’t require 20 pages and 15 sources to explain because the elements are more limited and unambiguous.

My previous assumptions about essays were so much simpler. I had thought that they should maintain a modicum of decency, and yet “Jay’s shockingly hairy ass” (Hough, 27) is not that. Also, Hough’s work is purely subjective with no pretense. The typical person might furrow their brow upon hearing that it is an excerpt from an essay. Over the eight days of the Summer 2024 Residency, I learned that “Jay’s shockingly hairy ass” (Hough, 27) equally belongs in Hough’s book of essays as it does in a memoir or fiction. Subjectivity is a feature that does nothing to help a reader recognize the genre.

It gets murkier.

Jenn Tatum, writing for Marginalia, the graduate student blog at Columbia College Chicago, said, “An essay doesn’t know where it’s going, doesn’t know its end result (Tatum).” This personification of an essay, as if to have a mind of its own, suggests the qualities of a vagabond, which is not particularly reassuring. Certainly not concrete.

Robert Atwan (2012) does his best to confuse the issue. Atwan was the series editor of The Best American Essays for 38 years, from 1986 to 2023. If anyone can clarify the definition, it’s Atwan. He writes in a journal article, “Notes Towards the Definition of an Essay”:

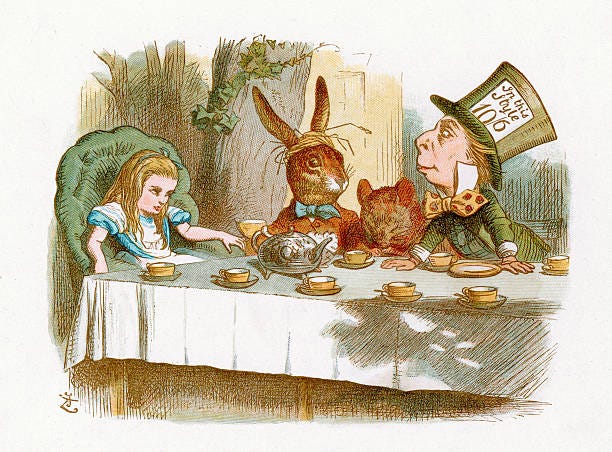

The essay’s literary identity was almost totally lost early in the century, and the word has, as Lynn Bloom [Distinguished Professor and Aetna Chair of Writing Emerita at the University of Connecticut] aptly noted, become a catchall for any sort of nonfiction prose. A collection designed for a short-story course, for instance, would not contain memoirs and creative nonfiction, nor would a poetry anthology feature journalism and reportage. But in Alice-in-Wonderland fashion, an essay can be whatever anyone claims it is (Atwan, 113).

A “catchall,” said Bloom. It reminds me of the teacher who tells every one of her students that they are special, which makes no one feel special. If I were an essay, “catchall” wouldn’t boost my morale either.

As a decades-long leader in critiquing the essay, Atwan references a bizarre child’s fantasy story to describe what has become of the genre. What are we to understand about it if the literal and figurative rabbit hole down which Alice falls represents her descent into an unexpected and bewildering exploration of the subconscious mind? The definition remains liquid. It isn’t the reference to the story itself that mixes up our understanding, it’s that Atwan (113) uses it to say “an essay can be whatever anyone claims.” It would make for a fascinating roundtable discussion to interpret, or perhaps more aptly, ponder, what Atwan’s message means specifically. It might help to locate some concrete details, or it might not.

Madhatter’s Tea Party (Photo: Getty Images)

More recently, Thomas Karshan, a professor of literature at the University of East Anglia, penned an essay called “What is an Essay? Thirteen Answers from Virginia Wolff.” He said: “Essays have always understood themselves evasively, preferring to define themselves by what they are not. They are not quite knowledge, and they are not quite art (Karshan, 37).”

Oh, boy. Could there be a more lost individual? Combine the three uses of personification to describe this genre of writing, and our person doesn’t know where she is going, doesn’t know who she is, and her identity is better understood by what she is not than what she is. If the essay were a person, she’d be on a mental health watch list. Or tripping on mushrooms. Or, “whatever.”

I was not exactly accurate in my delineation of an essay and memoir on that first day of the program. I wasn’t wrong either. I was partially right, depending on the audience. After all, even those who have steeped their entire lives in the craft are as rigid as jellyfish in defining the genre. Maybe by virtue of its atomistic complexion, an essay doesn’t exist. Maybe the subgenres of essays should proudly stand on their own feet, uncomplicated and whole as individual genres. Maintaining the experts’ use of personification, critical essays would stand firm with their feet apart, holding clipboards. Historical essays would face the past and hold banners of time and place. Academic essays would work ever harder in their slavery to form. Personal essays would sit cozily by the fire in a cushy chair and dream of being a wealthy memoir. Everyone would know exactly what defines them. Instead, the essay is all of them.

If an essay can be everything, then is it nothing?

Perhaps I can take solace in this pervasive ambiguity. Maybe my partly accurate explanation on that first day of the program was not cause for shame, given that my definitions grew naturally from my profession as a high school English teacher. In my world, my definition was spot on. Maybe even generously loose.

^ ^ ^

“Writing nonfiction is more like sculpture, a matter of shaping the research into the finished thing.”

Joan Didion, 1977 (Photo: Associated Press)

A Reinterpretation

Atwan’s allusion to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in working toward the definition of an essay has another possible interpretation. As I said earlier, it’s true that it suggests the genre is a descent into an exploration of the subconscious, but the rabbit hole also symbolizes the potential for adventure and the wonder of new experiences. It’s true that it symbolizes the unexpected and bewilderment, but it also leads to looking more closely at our lives’ transitions, the mockery of social conventions, and hope for a better life. It may be a disturbing story with wild and unreal situations, but there are constructive interpretations.

In an article called, “Celebrating 150 Years of Alice in Wonderland,” Rachel Hatch writes for Illinois State University’s online publication, Redbird Scholar: “An Oxford University professor of mathematics, Carroll filled both Alice books with numerous references to mathematical puzzles and philosophical debates yet kept it engaging for children (Hatch).” Hatch’s key words are “puzzles,” “debates,” and “engaging.” They begin to crack open a quality of the essay that revolves around the unsolved or perhaps incomplete. Hatch identifies features of Carroll’s fiction that engage readers by inspiring them to carry ideas and themes away from their reading chair, beyond the simple telling of the story. Jan Susina, professor of English who researches and teaches Carroll in children’s literature courses, says, “Our culture reinterprets the Alice books, just as we reinterpret Shakespeare and fairytales (Hatch).” Susina suggests that the success of the Alice books is in part because audiences continue to engage with them.

Atwan’s choice of analogies doesn’t help us gather concrete elements of the essay; rather, it emphasizes that there is a relationship between writer and reader that engages the reader to think about more than what is being said. Whether Atwan meant that specifically or not, Alice in Wonderland initiates a conversation, and perhaps that is what he meant in his title: “Notes Toward a Definition of an Essay,” instead of “The Definition of an Essay.” Maybe the whole point is not to set conclusions to the standard of total conclusiveness. Maybe an essay is partly defined by not declaring a final truth but opening the possibility of new questions.

Not to make too much of a single allusion by a single essayist working towards a definition of an essay, but Atwan and the others touch on a less tangible quality of the genre that begins to help me fashion a more three-dimensional and recognizable structure.

^ ^ ^

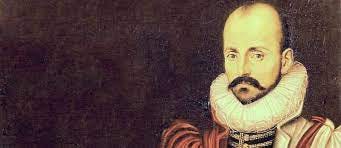

“I speak the truth, not so much as I would, but as much as I dare; and I dare a little more as I grow older.”

Michel de Montaigne

Truth and Reality

A hundred and seventy-five years ago in 1994, I was working on a bachelor’s degree in the University of Washington’s unique Comparative History of Ideas program, or CHID. It was a degree focused on examining ideas across disciplines and historical contexts. The program emphasizes experiential learning and self-reflection, and I clearly remember a time when self-reflection was foisted upon me during my final presentation in CHID 205, Method, Imagination, and Inquiry.

Recently: CHID on the beautiful UW campus. Prof. Phillip Thurtle on right. (Website Photo)

The classroom was small with about 12 other students, the lights were dimmed (or maybe that’s how I remember it), I was at the front of the class, and my presentation was in the question-and-answer phase. That’s when it happened. The word “reality” slipped out of my mouth like an old man’s dentures. In most circles outside of a university, the word isn’t always loaded. In the university setting, it’s at least twice as likely that someone will call you out for it. In the CHID program, students were required, with venomous saliva spilling forth, to challenge my chutzpah. Jack pounced: “Reality? What is reality?” I don’t remember the guy’s name, so I’ll call him “Jack.” He was the first to summon a response from me. He was pale with orange hair, stood about 5’11”, and had piercing but friendly blue eyes that made him look attentive rather than intimidating. If I saw him at the pub, I’d recognize him.

“Uhh,” and I paused just long enough to qualify for a pause, and out beyond left field somewhere near Oklahoma came a response not conjured by consciousness. I said, “Reality, inasmuch as one can predict it.” I literally said that. I was happy with myself. I couldn't say where that shit came from, and yes, I remember the wording verbatim because when he asked the preordained question, I wasn’t ready but immediately knew my error. Not having stammered in a moment like that is a memory I don’t forget. Nonetheless, my face felt hot because words like “reality” and “truth” were, and probably still are, curse words. I had broken a CHID code, and my whole body felt it. I continued to argue my point. I don’t remember exactly what I said next, so to be clear, this is a favorable paraphrase that is almost certainly more eloquent and confident than I was in that moment: “Gravity is technically a theory, but I think we can all predict it will be here if you jump from a 12-story building. In that sense, gravity is reality.” At the time, I didn’t know if I was talking out my ass or if I thought on my feet in an impossible situation and impressed the hell out of everyone. I still don’t know because I blanked on the remainder of the presentation. I suspect it was more the former, so I have since scrubbed it from my memory to stave off the possibility of knowing the reality. Oops. There’s that word again.

One thing I’d like to say about this story is that Jack was brilliant and kind. When he asked the question, it wasn’t a gotchya moment for him. It was a good and fair question I deserved to be asked. Jack was, and presumably still is, a good person.

The second thing I’d like to say is that the most truthful element of that story is not the simple facts, such as the name of the course, the number of students, or even Jack’s hair color. Trust me, it was orange. Those are factual truths, but where the question of truth becomes intriguing, mysterious even, is in the attempt to inform my readers, you, which emotions I experienced without telling you which emotions I experienced. That is, I needed to be sure that you knew I felt angst without telling you I felt angst. The goal was for you to know how I felt, precisely, 175 years ago in 1994 at the University of Washington—and unflinchingly believe it.

If I told the story right or, rather, honestly, then readers know that I felt angst, fear of ineptitude, dread, and momentarily confounded, without my saying so. I want them to know that I felt a little proud of my clever response but uneasy about the blackness that followed. The essay, in terms of that 15-second episode in my life, should develop trust between myself and my reader.

Reliability is necessary for any writing, of course, but a personal essay needs to be so while conveying an entirely subjective experience by a single person for an event that possibly lasted only 15 or 20 seconds 30 years ago. One might legitimately ask, Who cares? It may be the most unreliable form of writing. So, I ask again, why invite the old, stodgy Academic Essay to stand rigidly under the same umbrella when he is in so many ways the opposite of the trendy new personal essay, which is reliable.

Maybe honesty is a better word than truth. Maybe that’s how we marry the two, or at least get them to room together. It doesn’t come with the baggage of dogma—what is truth? And, honesty is an adjective, which allows both writer and reader to have a discussion around the descriptor, whereas the so-called truth is an historically effective way to pick a fight or start a war. Old Man Academia is nothing if not honest, and if he isn’t honest, he gets blackballed from the university. He is even happy to invite his readers to verify his truths. The pact is well-established. The personal essay wants fewer rules and has less desire to justify her truth with journal articles or demographic studies. The personal essay, too, is nothing if not honest, so the personal essayist—given that his content could just as well be fiction—must make a similar pact. While the outcomes of academic and personal essays possess dichotomies (i.e., objective vs. subjective, factual vs. experience), the focus on being impeccably honest is inherent in the writing process of each. In this way, we have found one way that both subgenres belong under the same genre umbrella.

^ ^ ^

“To speak the truth truthfully to one another is not only a delight; it is close to the core reason we exist in the first place.”

Friar James V. Schall, Society of Jesus, 2012 (No photo credit on National Review Website)

An Alliance

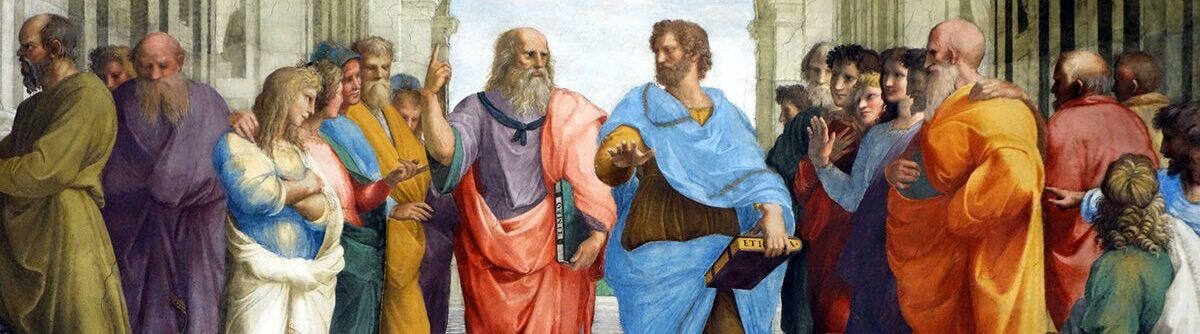

The creation of the modern essay has been attributed to Michel de Montaigne because he merged personal reflection and a more conversational tone with the Western tradition of intellectual inquiry. Prior to Montaigne, over 400 years ago, shorter written contributions not called essays were put forth by thinkers like Plato in Ancient Greece, Cicero in Ancient Rome, along with thousands of others from every continent. An essay, regardless of its etymology, has been a fundamental part of humanity since our consciousness rose up and demanded to be heard. The pact a writer makes with the reader includes early thinkers who didn’t write essays, per se, but who nonetheless expressed what they saw to be truths through short, nonfictional pieces of writing.

Raphael - Raffaello Sanzio | ~1510 (Public Domain)

In a previous section, I discussed how Atwan and others define the genre by referring to its “catchall” quality. They often use vague and abstract language (and personification) to say that the essay aims to engage and invite the reader to the thinking of the writer. Montaigne deliberately mixed that invitation into his essays without trying to achieve absolute conclusiveness, as if to say, “This is not all. Tell me what you think.” From the same journal article, Atwan explains:

Montaigne settled on the word essai to characterize his literary efforts...The etymology of essai can be traced to the late Latin exagium, which meant "to weigh" or "a weight." By the fourth century, the term had spread to the Romance languages with the additional and modern meaning of "to attempt" or "to try." Though we normally translate the title of Montaigne's book as Essays, suggesting only the genre, we should remember that in his time the term suggested no literary genre and would be read as "attempts" or "trials," or, since the verb essayer had a wide spectrum of synonyms, it could also suggest: to sample, taste, practice, take a risk, to experiment, to improvise, to try out, to sound—and these are only a few ways we might understand the term Atwan (2012, 109).

Anyone who has gone to high school would likely agree that their essays were “practice” and a “taste” of a broader subject (109). That they “weighed” an idea for 3-5 pages. Both the stringent academic paper and the liberated personal essay have a devotion to honesty. Both “weighs” limited and specific ideas (109). And if you continued to read and write essays after high school, this makes even more sense.

Because essays are a person’s attempt to make a brief and specific idea available to readers, those who wrote before Montaigne did so for similar reasons. The context of time and place in which they lived, of course, meant that they had their own edifying and unique way of considering it. Atwan writes that the “ancient Greeks and Romans, who developed the approach to an essay, although they didn’t call it that, with much stricter expectations, such as a commitment to objectivity, or...euboulia, that is, the capacity to give good advice, or for sound judgment (Atwan, 116).” Whether an essay does or does not explicitly offer advice, it demands sound judgment.

Aristotle spoke of eudaimonia, which alludes to the process of living virtuously. In modern psychology, eudaimonic well-being emphasizes meaning, purpose, and personal growth. These therapeutic emphases are consistent with writing essays. Ancient Western writers were ardent in their search for meaning and truth, for which their written works had exemplified.

I could continue for volumes identifying the perspectives of writers from all around the world who expressed their individual ideas. Whether they strived toward strict objectivity, as the ancient writers and all those who followed their precedent did, or if they were Montaigne in 1570 and the writers who followed his break from convention, they all had something to say and are still read today because they forged a pact with their readers, and the readers read with confidence.

^ ^ ^

“If you’ve met one person with autism, you’ve met one person with autism.”

Dr. Stephen Shore (Spectrum website)

What an Essay Is

As human thought developed throughout Europe (and the West) since Homer’s epic poems around the 8th century B.C.E., it took an incredibly long time for the writers who followed to merge their own voice with intellectualism. Montaigne was the first to succeed 2,400 years later. Also, how would the history of ideas have been different had Plato and Aristotle followed Socrates and insisted on the Greek oral tradition of “puzzling” and “debating” their ideas? Ideas alone are like vapor whisking around in our skulls, and unless we attach words to them, our identities are abbreviated at best. When we speak words, our identity gains a more full voice. The need to be heard is inherent in all of us. It was inevitable that, even if Plato and Aristotle had emulated Socrates and only spoken their minds, someone else would eventually write down their thoughts in order to make them real and permanent.

It is astonishing, too, how devoted to intellectual integrity writers had been. Aristotle’s eudaimonia and Plato’s euboulia are only two ideas that flourished. In the 5th century A.D., St. Augustine wrote over five million words while living in northern Africa. In the 1200’s, Thomas Aquinas wrote 2,900 pages in a single book so he could answer 614 theological questions in 3,125 articles. All of them followed the same language within the language of integrity. Virtue. Duty. Discipline. Objectivity. They wrote exhaustively toward honesty and truth to convey ideas from mere wispy thoughts to eager and passionate readers. Atwan writes that “it remained this way throughout the West until the late 1500’s when Montaigne” showed up and said, in so many words, “Let me tell you what I think, and how I came to think it.” And he did. He pissed off a few people for inserting a subjectiveness that had been mostly avoided, but he did so with enough fidelity and enthusiasm that it stuck.

Sitting comfortably at my desk centuries after all of them with the infinite expanse of information in my pocket, it’s unsurprising that the Montaigne sprung the power of the subjective voice when he did.

Consider:

Europeans hid miserably from vengeful kings, queens, and the Christian god for at least 1,200 years in the Dark Ages for attaching words to their thoughts; and then the printing press was invented in 1440, which gave way to literacy.

One lifetime later, heretic and outlaw Martin Luther applied this new literacy by alternatively interpreting the Bible and posting 95 theses on a church bulletin board. The Pope declared his own singular interpretations, while Luther suggested others. This in turn loosened the Church’s grip, and other freshly literate thinkers suggested newer interpretations. Soon the Pope had to compete with a dozen new voices. Perhaps this is where subjectivity took root.

The Renaissance cleared space for the Enlightenment in the 1600’s, which was the same timeframe that Montaigne added his voice to Western intellectualism. Or put another way, the Church finally loosened up their assholes and the capital “I” Individual could say it out loud and without recrimination.

This worthy recipient of God’s wrath wrote a poem questioning his purpose in life. (Getty Images)

In a more progressive Europe, Montaigne was empowered to declare himself worthy of acknowledging that he had been listening to the conversation and said this about his essays: “I offer them as what I believe, not what is to be believed. I am here only at revealing myself, who will perhaps be different tomorrow (Nixon et al., 2024).”

Maureen P. Heath (2019) writes about a chapter in her book, The Roots of Christian Individualism:

Montaigne looked inside and sought self-knowledge as a step toward self-acceptance in the temporal domain. The chapter [in her book] highlights the subjective-self meme as a turning point towards modernity, where we define our individuality in our differences. Montaigne turned from humanism as a basis for life, to the human values he found within himself and this is a mark of a more modern individuality (Heath, 181).

Perhaps an essay is so difficult to nail down because it’s one word trying to describe the unique ideas of countless individuals1 .

In 1935, Katherine Fullerton Gerould wrote an essay called “An Essay on Essays,” and writes, “The essayist says, ‘Come, let us reason together.’ That is an invitation—whether given by word of mouth or on the printed page—that civilized people must encourage and, as often as possible in their burdened lives, accept.” (Gerould, 117) The genre that Gerould describes sounds like more than “attempts,” “trials,” “tastes,” or “practice.” An accepted invitation to read an essay, whether a rigorous academic journal article on the ethics in the development of artificial intelligence or “Jay’s shockingly hairy ass,” is an RSVP to which the reader agrees in good faith (Hough). S/he expects that the writer will honor that.

I am 59 years old and grateful for the lifelong educational opportunities I’ve had, including my experience as a high school English teacher of twenty years, but I walked into Goucher College’s Creative Nonfiction Writing program without a clear idea about the partnership that essays demand. The essay was labeled by a distinguished professor of English, Bloom, as a “catchall.” Tatum says the “essay doesn’t know where it’s going, doesn’t know its end result.” Karshan says that “essays have always understood themselves evasively.” They define the genre like this because the essayist is not writing to emulate the other but to expand and share a sliver of the self. “In the fashion of Alice-in-Wonderland, an essay can be whatever anyone claims it is (Atwan).” Whatever.

If you’re an essayist, it opens the fields by miles; however, be mindful that you’re making a pact with the reader, so whatever you write, be honest and make no pretense.

^ ^ ^

1 I borrowed this notion from advocates of people on the autism spectrum. The original goes something like this: “Autism is one word trying to describe millions of stories.” It helps to clarify the epigraph for this section. Who to credit for this quote is unknown.

Reply