- John C Flavin | Personal Essays

- Posts

- "Mr. Grad"

"Mr. Grad"

After I had set his hair on fire, figuratively speaking, he told me to leave his classroom forever and that I needn’t go to the office to appeal for reconsideration.

Not political

Topics: Life story, humor, class clown, teaching, parenting, family, human interest, Ferndale High School, the 1980’s

Imagine if, from the beginning, American schools had always created learning spaces that nurtured a child’s dignity and well-being first. As a teenager at Ferndale High School in Michigan in the early 1980’s, I lacked an awareness of the practical things that other kids used to plan their future. What did I want to be when I grew up? I couldn’t imagine because I never thought about it. What colleges would I apply to? College?

I don’t recall being asked these questions: not by teachers, not by parents. A few classmates chose private colleges, while others went to middle-of-the-road schools. Some aspired to bigger names, like Michigan State or the University of Michigan. Many didn’t go to college at all, and some settled for higher learning institutions with fewer barriers for admission. I waited until after graduation to make plans to attend Oakland Community College, three miles from where I lived. Most of my friends had family or other adults at school who helped them choose the universities that matched their GPA and SAT scores. I had little to no understanding that grades and standardized tests were related to college because my GPA was 2.0 and I didn’t take the SAT. I knew there was a relationship, but assigning value to any of it was not part of my thought process because the conversations didn’t come up. Homework? Never. The importance of being present and the completion of assignments? I skipped what I could get away with and did as little work as possible.

I was, however, aware of the school’s attendance policies. Ferndale High allowed seven unexcused absences plus five tardies, but if we reached eight absences or had seven plus six tardies, there was no negotiating with admin: we failed the class. Despite my clear understanding of the numbers and close attention to my attendance record, that was one of the ways I had I lost credit for a course.

Recently | Front (Photo: C & G Newspapers)

Mr. Basil Hall was my antiseptic, fussy, and lipless 9th grade algebra teacher with a twangy Southern accent and a daily white, pressed button-up shirt. At the time, I was convinced that he failed me because he had no sense of humor. Or maybe I didn’t perform well on the quizzes and tests. Maybe both. Either way, I didn’t like him, and he didn’t like me.

Other students who did have answers to important questions and participated in school spirit events would sometimes paint inspirational words on big pieces of paper and hang them in the hallways or the commons. Focus! Commitment! Perseverance! Courage! The coaches of the sports I played marched out the same singular ideas, for which I also had no practical use. I played football and baseball because I liked playing sports. I quit wrestling after 10th grade because I stopped liking it. I put no thought into what I was supposed to do differently after seeing the motivational words.

Any school, USA, so long as the mascot has paws.

I was motivated socially, though, and was therefore typical in my awareness of girls, hanging out, going to parties and dances, and doing almost anything to get other people’s attention; there were easy opportunities to be a class clown. On the surface, I appeared impervious to sadness, but underneath, I was compensating for something.

As a two-year-old, when my mom and dad were still together, they’d have these small parties, inviting a couple or a half-dozen friends after putting me and four siblings to bed. I was the youngest, and all of us were under 10. They’d put on Mose Allison or Miles Davis records, play spades or pinochle, drink, and smoke cigarettes. They weren’t exactly beatniks, but they read a lot, including Kerouac and Kesey. They weren’t necessarily bohemians, even though some of them were artists, including my dad. All of them were socially liberal, so I doubt they would have been crushed by either label.

Mose, 1960’s

A few years before my dad died in 2016, he told me a story about one of those nights. I had climbed out of my crib and out to their card game in the dining room. This was in 1968, when having five small children in the house wasn’t reason enough to avoid filling it with second-hand smoke. They’d put me back in the crib, but I’d climb out again and again so I could hang out with them. One night I tried something new: As toddlers often do, I thought if I couldn’t see them, then they couldn’t see me. He said I climbed out, grabbed a stray diaper, draped it over my head, and crawled slowly in their direction across the kitchen floor as if to clandestinely mingle. They were light-hearted about it, laughed, and, once again, returned me to my crib.

I was still shitting my pants, and the power of positive reinforcement was carving grooves into my neural pathways. I learned early that I could be rewarded for getting people’s attention, so I pursued similar rewards later. I’d get my mom’s and her visiting sister’s attention so they would watch me do something nonsensical, such as flopping like a fish on the shag carpet or making a series of silly faces.

They’d offer the default response, “Oh, you are so silly,” but here’s my advice to new parents: Don’t encourage this behavior in your own children. This is a brief phase in their development, and you need to prune it at once. Laugh one time, if at all, and be brutally honest: “Okay, that’s enough. It was funny maybe once.” Adjust your language to comply with your personal parental philosophy, but don’t curse your children with the delusion of permanent cuteness by positively reinforcing nonsense. If their integrity isn’t reason enough for you to nip it while they’re little, then do it for yourself. You may spend their childhood shaking your head with tight lips and gritted teeth as they cling to a grandiose sense of self.

In first and second grades, I had Mrs. Washington, and she didn’t think I was cute at all. I’d leave my seat without permission or talk too much. She would tell me to put my hands on the desk, palms up. Then she’d smack them with a ruler.

In seventh grade, we were in transition during Ms. Surowka’s math class. Everyone was milling about after a quiz and, on a dare, while she went over results with the diligent kids, I got on my hands and knees and bit her ankle. In a start, she yanked her foot and yelped, “What are you doing!” I didn’t break skin, nor did I intend to, but I got the desired result: lots of laughs from classmates.

I suppose it’s better to be labeled happy than miserable; I’m not sure. Any singular label has the potential to cause a child trouble because s/he often spends years trying either to live up to it or to shed it. I believed that everything I did would be cherished and adored, and I only started to realize how generic I was after moving to Seattle when I was 20. I had lost my entire social network and ran into the buzzsaw of impartial adults who didn’t know me. Class clown suddenly became my top accomplishment up to that point, and that tidbit of information was best delayed in conversations with new and unfamiliar people. My identity had dried up.

My parents were good people. I’m grateful for most of what I learned or inherited from them. It’s easy to say after the fact, but I used to wish they had had higher expectations. My mom, though she loved me unconditionally, battled depression and was too worn out to impose hard and clear expectations after a decade of raising four older siblings. She found out I drank when I was 15, but she didn’t reprimand me. Instead, she waited a day and asked, “Why do you drink?” I told her I didn’t know, so she pressed a little further.

I said, “To be happy, I guess.”

“You’re not happy?” she asked. I didn’t have an answer, so we settled for no answer since neither of us believed I was unhappy.

While in his seventies, my dad said to me, “You’ve always been the happy one.” Always, he said, forty years after my childhood. His quintessential line was, “Whatever happens, happens.” Not in the “it is what it is” sense of resignation, but in the “it’s all good” sense of easygoing acceptance. That about sums up his fatherly presence. “Happy” was good enough so he didn’t follow up with a question like, “Were you happy?” If he had, he probably would have hit the same wall of denial I put up for my mom.

I spent early adulthood wondering where all the childhood adoration had flown. I spent my school-age years reinforcing the happy label, and it took a couple decades to pick apart the pieces so I could decide what to do with them. A person may have dignity and therefore find happiness, but a happy person doesn’t necessarily have dignity. My father’s father left him when he was two and returned on his son’s 14th birthday without a word of explanation. My grandfather was a good man, too, but his fatherly presence was missing in action. I wouldn’t say my dad ever injured my dignity, but he didn’t nurture it either. He didn’t teach me to be obnoxious, but he didn’t condemn it. Whatever happens, happens.

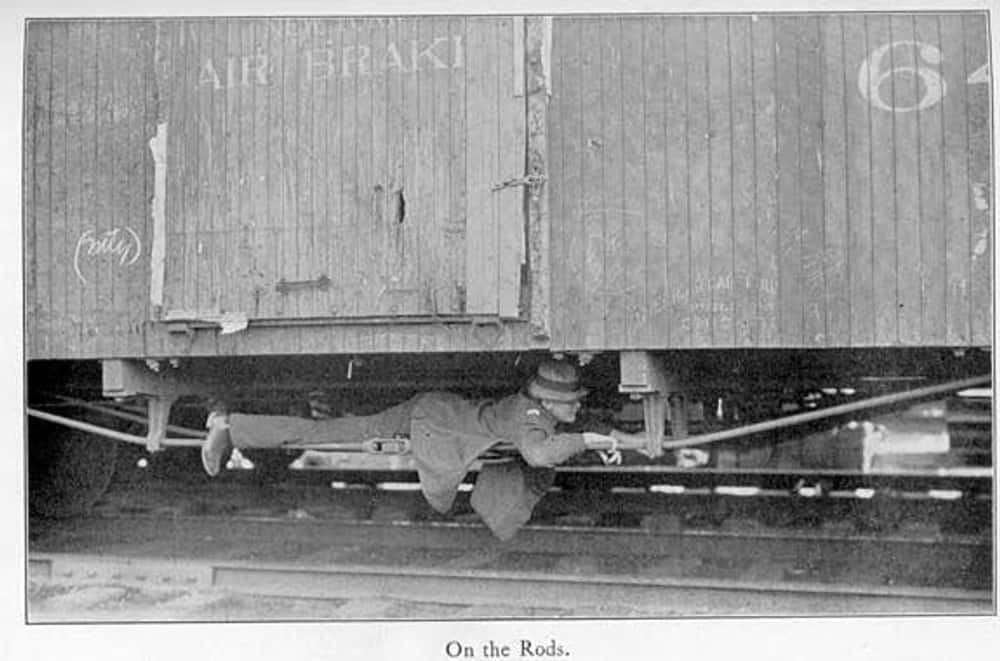

Grandpa Flavin rode the trains from Detroit to Seattle at the beginning of the Great Depression, two years after my dad was born in 1929. In 1941, he returned on my dad’s 14th birthday. (Photo: Public Domain)

^ ^ ^

In my junior year of high school, my antics caught up with me. I had failed humorless Mr. Hall’s math class, lost another by way of excessive absences, and then I failed a third class, this time for behavior in geometry with Mr. Grad. After I had set his hair on fire, figuratively speaking, he told me to leave his classroom forever and that I needn’t go to the office to appeal for reconsideration.

Some other kid must have pushed Mr. Grad’s limits, too. He must’ve been kicked out and had persuaded the administration or counselors to force or sway Mr. Grad to give him another chance. Why else would he hint at the possibility? I figured I was toast and that was that, so planting that seed could have backfired on him; I wouldn’t have thought to tell Principal Dzyacky after I blew up his math teacher’s daily plan. Mr. Dzyacky might have heard me out, too. He was the kind of principal that students felt comfortable around, unless they were in serious trouble. Anyway, I wouldn’t have gone to him for help because, to me, that would have been like telling the cops I’d robbed the corner store and then asking for a ride home with the cash still in my pocket. I was an absolute asshole to Mr. Grad, so not being re-admitted and having to retake the course was a foregone conclusion.

In the same way that I had lost credit for missing too much class time and for failing Mr. Hall’s algebra class, I accepted the third failed course without a word. What motivated me to be a class clown was the desire to maintain my “happy” label; what caused me to neglect my own self-interest—that is, getting a diploma and doing well in school—had more to do with having a dad with the ambition of a chaise lounge. He held himself to a strict standard of happiness and physical comfort, and decades later he self-identified as a hedonist. Zero interest in hard work or making a living, so long as he had enough. Getting kicked out of class in the way that I was, and paying no mind to consequences, fit that model.

Mr. Grad was about 5’10”, his body narrow from head to toe. He had a hawkish nose and a full head of frizzy to curly hair that reached upward and outward about five or six inches from his scalp. It was fairly normal in the 70’s and 80’s to grow big heads of hair. I can still remember a little hop in Mr. Grad’s voice as he coordinated his narration of math terms with marking the chalkboard, striking barely yellow x’s and y’s, arcs, arrows, and perpendicular lines. In a perfect world, he’d have taught only the well-behaved honors and advanced students. He may or may not have been the most inspirational teacher, but he would have been effective because he wasn’t jaded by teaching his subject. I have little doubt that he would have been able to connect with dozens, if not hundreds, of young people.

AI: male teacher with big curly hair facing chalkboard marking math equations.

In 1983, classroom management strategies were not ideal for responding to unruly and thoughtless youth like me. We either obeyed or failed. If we disobeyed repeatedly, it almost didn’t matter what caused the student’s delinquency, we could have been permanently expelled from high school. That’s how Mr. Grad was able to remove me from his room without bringing another adult into the conversation.

On the day I got booted, an idea had materialized to antagonize him in a way that I believed I couldn't get caught. I sat in the center of his room with the desks neatly squared off in rows and columns, which was like an arena stage for me to entertain the other students, all of whom were within a few feet. In the days of chalkboards, Mr. Grad’s first disadvantage was that his eyes faced away from the class, and the second was that he was busy synchronizing the stick of chalk with verbalizing the symbols and figures.

Desks neatly squared off in rows and columns. Killing dignity and an institution in American education since 1900. (Photo: public domain)

While he talked and marked the board, I made a low-volume humming sound made up of Ds and Ls, as if to say luddle-luddle-luddle quickly, repeatedly, until he stopped talking. When he started talking, I would luddle; when he stopped, I stopped. In my perfect, imagined scenario, it would be difficult for Mr. Grad to ascertain whether he heard anything at all, and that uncertainty would make his frustration visible, and that visible frustration would make the gag complete. Ideally, it would have been impossible for him to pin it on me.

He didn’t respond the first few times, so I got a little louder. It didn’t take long before he turned around in a knee-jerk manner. “Who’s doing that!?” When no one fessed up, he kept his head turned toward us while his body slowly returned to the chalkboard. Then he carefully turned his head and uttered more geometric terms and equations, so I started: “Luddle-luddle-luddle...”.

He spun around and repeated, “Who’s doing that!” Then he warned, “If I figure out who’s doing that, you are done here!” I was in class clown heaven, made giddy by the desired stimulus and instant reward. I had the entire class’s attention, and I was sure that he’d never know it was me. Even if he did accuse me, how could he ever prove it? He studied the faces before him while I fantasized that this game could go on for the rest of the school year. But he quickly erased that vision and pointed, looking every bit like the afflicted Puritan unmasking witchcraft in Salem, Massachusetts some 330 years ago. He resounded at last, “You!” Then he wound up his arm as if to recharge the energy needed to repeat the indictment. His arm fully extended, and finger stiffly pointed toward my face, Mr. Grad proclaimed, “It’s you!” I think he was simultaneously bursting with joy and about to erupt into untenable anger.

“Me? It’s not me!”

He took slow steps toward me, which added to my sense that he absolutely knew it was me, and even if he didn’t, he wasn’t going to hear my cries of innocence. I nevertheless continued to cry my innocence.

He didn’t give me a chance to bargain my way out of it, though. “Out! Get out of my room!”

Other students never said it to my face, but I have to assume that at least a few were exasperated by me. Years later, it occurred to me that a classmate must’ve nodded their head in my direction with accusing eyes because I have always thought it peculiar that he had asked twice who was making the sound and waited a solid 10 seconds before pressing me into his crucible with inexplicable confidence. What else could have triggered his sudden certainty that it was me? It’s also possible that he detected a slight shit-eating grin on my face, or maybe I overplayed my saintliness, or maybe he didn’t care if he was wrong—this was his chance to get rid of me. Regardless, Mr. Grad only had a handful of faces to analyze as likely culprits, and mine was first among them.

While he bolstered his vehemence, my false denial diminished. We bickered back and forth while I gathered my things. When I reached the doorway, I stopped and looked back to my classmates for confirmation that I was hilarious. The positive reinforcement taunted Mr. Grad. I still had a foot in the room and was still high with adrenaline. For Mr. Grad, I couldn’t leave the room fast enough. He showed his stern face and pointed toward where the school’s office was if we could see through the white-painted cinder block walls: “I don't care where you go! Don't even think about coming back! You can tell the office anything you want...you are not stepping foot in this room again!”

I looked in the direction he was pointing, then I reached into my pants pocket, pulled out a dime, placed it on my first finger and thumbnail and flipped it in a silver-twinkling arc that landed on his desk calendar and came to rest. “Don’t spend it all in one place,” I said, and then I turned around and walked into the unknown. He was still screaming at me when the slow-closing door obscured his words.

It took a few hours for the adrenaline to subside and be able contemplate what had happened. I knew right away that I was an asshole. It’s who I was at that moment, and I didn’t feel bad about it. I felt good about the attention and rewatched highlights of my perfect coin toss in my mind’s eye.

High school students have always suffered from this kind of ignorance because that’s the nature of guessing one’s way through the most serpentine developmental transition of our lives: puberty and family dynamics. As happens with most people, I suppose, my consciousness increased when adulthood nudged me out of youth and then spent the next several years tapping me on the shoulder: John, pay attention. Instead of persisting in making other people’s lives miserable like I did with Mr. Grad, I became a teacher myself.

^^^

We faced the same psychological challenges in the 80’s that teenagers do today: depression, suicide, post-traumatic stress disorder, and others which were often exacerbated by OCD, ADHD, autism, and a dozen other common conditions. Classmates were sexually abused, had learning disabilities, and endured poverty and substance abuse. Persistent bullying was as normal as ever.

I had a close friend whose father was in prison. I had another close friend whose father, an officer of the law, beat him. One of my classmates, straight after graduation, married a man 30 years older. They each found ways to have pretty good lives, but that wasn’t true for everyone.

Frank Mason hung himself in a park with a bed sheet.

Olivia Thompson may have been on the spectrum, but if you said that to a counselor in 1983, they’d have said, “What spectrum?” The poor girl faced cruelty almost daily.

From the age of 10, Billy Sellers helped his paraplegic father go to the bathroom and waited for his mother to come home from the bar before he could go out to play; he later spent two decades in prison for armed robbery and lives with schizophrenia.

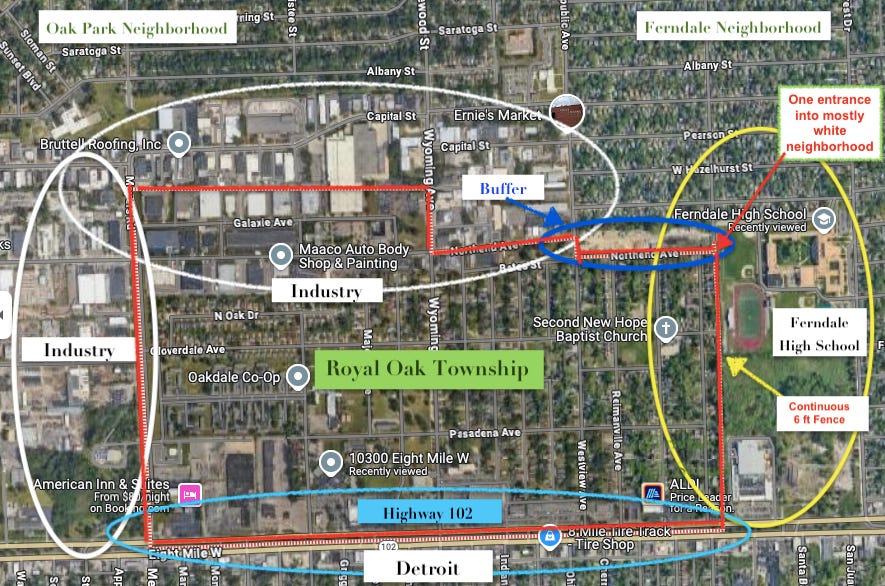

Most of the black students at Ferndale High lived in a bizarre, tiny, red-lined township—undoubtedly a holdover from the Era of Segregation—that had similarities to a Jewish ghetto. On two sides of the roughly square neighborhood stood 6-foot fences. A warehouse district graced a third side, Highway 102 (8 Mile Rd) partitioned the fourth, and only four or five roads provided access in or out, allowing for only one to lead directly into a white neighborhood.

2025 | Google aerial screenshot | Ferndale racial makeup includes 82.3% White, 5.6% Black or African American | Royal Oak charter township is 95.7% Black and 3.2% White

The impact of most of these imbalances, tragedies, and maladies were unknown, unaddressed, downplayed or misunderstood by teachers and parents. It was a time when mental health support was miserably inadequate, stigmatized, and often dismissed like a bad cold. Social-emotional problems existed among young people, but the strategies to address them didn’t. Obviously, teachers back then had compassion and constructive conversations about students who faced trauma and prejudice, but in 1983, getting at his or her deeper problem and talking about its connection to problematic behavior was more a matter of personal judgment. Educators in the 2010’s and 2020’s are “trauma-informed” through training in social-emotional learning, or SEL, and while these problems have always existed, today’s educators share a common language to discuss how past trauma impacts a student’s present experiences.

Mr. Grad was among a generation of teachers in the 70’s and 80’s who embraced the practice of doing all the talking. Everyone is familiar with teacher-centered instruction: Information passes from the knowing mind to the unknowing mind. Done. We can spot it in the way teachers organize the classroom. The desks in Mr. Grad's room, like most in America, were in straight rows and columns that faced him and the chalkboard. Ideally, students entered the room, sat still, listened, and took notes. Quizzes and tests would be scheduled at regular intervals. Anyone who attended public schools (and most others) knows this routine, regardless of age, and very few look back and think to themselves, “What a dignifying experience that was.”

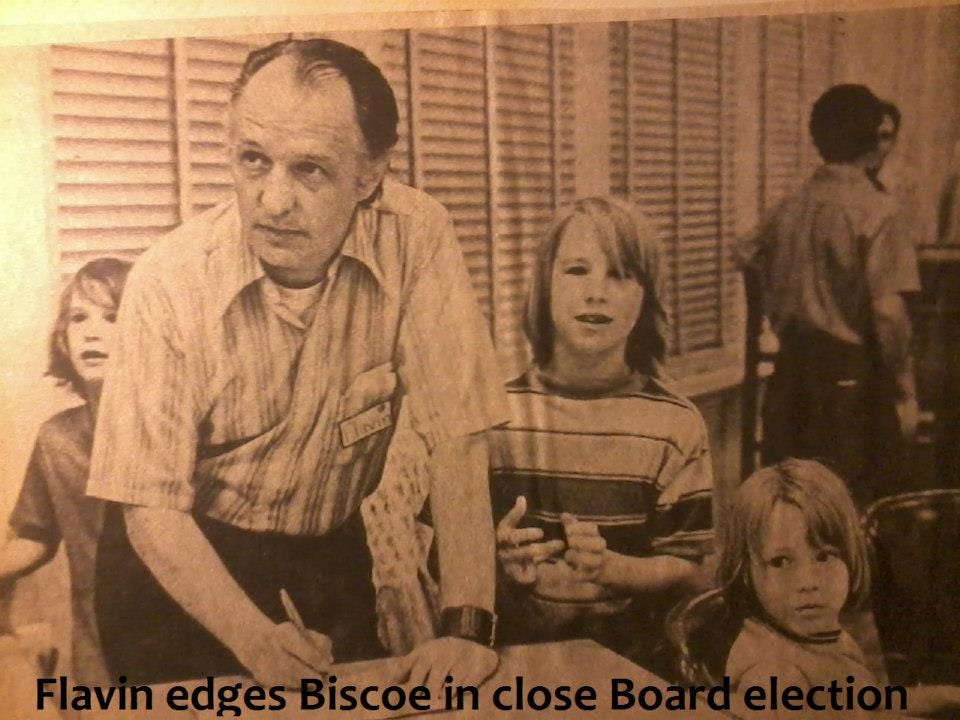

1973 | Flavin Family posing for Royal Oak Tribune newspaper article in the front yards as dad runs for President of the Ferndale School Board | L-R: Pete (8), dad (46), mom (44), me (7), Steve (11), Paul (14), Liz (15)

I’m not sure it would give Mr. Grad any solace, but having been that thoughtless student and remembering it so clearly contributed to my becoming a teacher. Over time, long after our last interaction, my childhood wounds buried in my subconscious mind when I was luddling had oozed into my conscious mind. Eventually, I became aware of a whole lot more than the obvious fact that I behaved poorly in 1983.

I was eight years old in 1974, the year my parents divorced. I had a familiar disengaged response when they broke the news: I laughed. My mom asked, “John, why are you laughing?” “I don’t know,” I replied.

That same year, my two oldest siblings quit high school in 9th and 10th grades and then lived permanently elsewhere. There was no explanation.

In 1975, I was molested by a neighborhood boy. Mildly enough not to traumatize me, per se, but enough to twist my sexuality and play a part in a few episodes of self-destructive behavior. I didn’t begin to own it until I was 31.

In that same year, my dad had campaigned and won president of the school board for Ferndale School District, and yet he paid $68 a month in support for three children and rarely asked us about school. No one acknowledged the irony in that. Not to me, anyway.

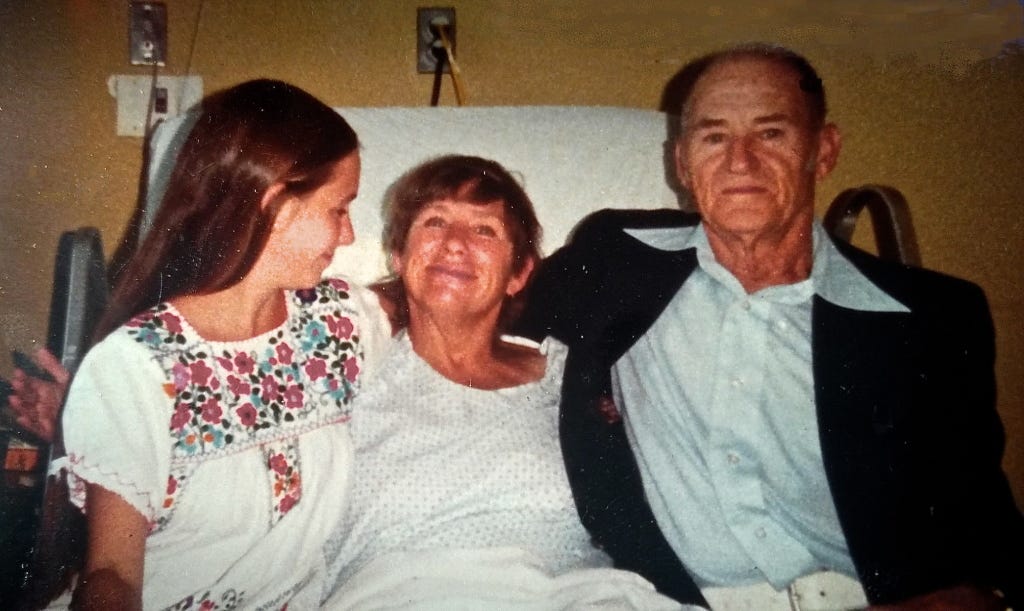

By 1982, during my sophomore year, my mom was diagnosed with lung cancer at age 52 and allotted eight months to live. Eight months later, she died. I was back in school in two days, and about a month after that, I gave Mr. Grad hell.

1982 | Mt. Sanai Hospital in Detroit, Michigan | Oldest sibling Liz (24) , mom (53), and Granddaddy (79)

Instead of living with my dad, I had two offers from friends’ parents. I stayed with one of them until I graduated. I did have a say in that because if went to Royal Oak to live with my dad, I’d have had to change of schools for my senior year. It was nonetheless evident that my dad’s girlfriend was done mothering1 .

Despite having my other classes in order, no conference was held regarding my behavior in Mr. Grad’s (or anyone else’s) class. I never spoke to a counselor about my mother dying, nor did a teacher ask, nor did I let on. No second adult knew about my assholish behavior because my mother had died, my father was busy being a friend, and my friend’s parents, with whom I stayed, didn’t receive a phone call since it was never reported to the office. Mr. Grad probably didn’t report it out of fear that I might worm my way back into his room, and I can hardly blame him. I didn’t report it because it hadn’t occurred to me to turn myself in. As far as Ferndale High School was concerned, I failed a class. It happens all the time. They reassigned the geometry course for my senior year with a different teacher. That’s all.

It’s not as if kids don’t fall through holes in today’s schools. They do. All the time. And conferencing did happen with adults in the 70’s and 80’s, but it was more likely for kids to fall through the cracks unexamined, and when the adults don’t examine the child’s psychological or personal development, who will? The child? Maybe. Maybe not.

Many students address their wounds with substance abuse. Some skip school for weeks. Some get depressed and never return. Others become violent and sometimes land in prison. I coped with my losses by putting on a happy smile and pretending everything was copacetic. I was a dick to Mr. Grad, and I didn’t care. That thoughtlessness, that striking lack of awareness of oneself and future, regardless of the reasons, is a hallmark of adolescence then and now. Public education deserves much scrutiny, and yet today it has indispensable systems that address a child’s well-being, a child’s life. Young people are fallible human beings carrying burdens they sometimes can’t carry and deserve to be educated with dignity, even when they make poor choices, and public education seems to be more aware of that now.

There was no excuse for my behavior with Mr. Grad, but was it predictable? I was the same as the millions of students who in 2025 still sit, listen, and take notes while managing wounds they may not know exist. I don’t fault Mr. Grad. Sure, in retrospect, he could have had better classroom management skills, and it’s ultimately on him that he took the bait from me. But he was the norm in 1983 and to a large extent still is. I don’t fault the educational culture of the 70’s and 80’s. They were amidst a century of precedent: teacher-centered, squarely organized, and punitive mindsets. It was what it was.

Imagine if, from the beginning, American schools had created learning spaces that nurtured a child’s dignity and well-being first. Our schools today have inched closer through student-centered instruction, social-emotional learning practices, and restorative instead of punitive mindsets, but they still drag around the anchor of last century’s teaching models.

I wasn’t a victim of the times; I was a predictable outcome. Until we transform what we do in education to address the child as a full human being with an innate right to dignity, our losses to standardized testing, smart phones, and chronic absenteeism will persist.2

1 Sue was an esoteric and wonderful person. She was done mothering. I asked her in my 40’s if she ever felt an urge to step in for my mom. Her response was immediate and flat: “No.” Sue was also honest, which I appreciated.

2 Standardized tests where half the students pass. Chronic absenteeism, which continues to rise. Teen suicide and depression rates that are higher than ever. Addiction to social media in which no one knows the outcome. Etc.

1973, Counting Votes | L-R: Pete, dad, Steve, me

Reply